When I was young I attended an AutoCAD summer camp (I was a pretty cool kid). The main ongoing project over the entire course of the program was to design and create a 3D model of a car. At the end of the camp, everyone got to take home a matchbox car-sized plastic model of their own car created by rapid prototyping. That was my first exposure to 3D printing.

Over the course of my adult life 3D printing has exploded in popularity. The technology has steadily improved and made its way into the consumer market. 3D printing has been instrumental in the development of Maker culture, and is an integral part of build spaces like the Idea Shop at my own university. There are online shops where people can post their designs for anyone to order. People like Henry Segerman have made incredible use of 3D printing for explaining mathematical concepts with visual and hands-on demonstrations.

The rise of 3D printing is one of the most significant technological developments to occur during my lifetime. It is a technology that truly has the power to revolutionize the world, and has countless applications in engineering and medicine. I am excited to see what its future holds, and would love to be a part of it, myself.

3D printing costs money, though, so I just cut up some old folders and glued them into shapes instead.

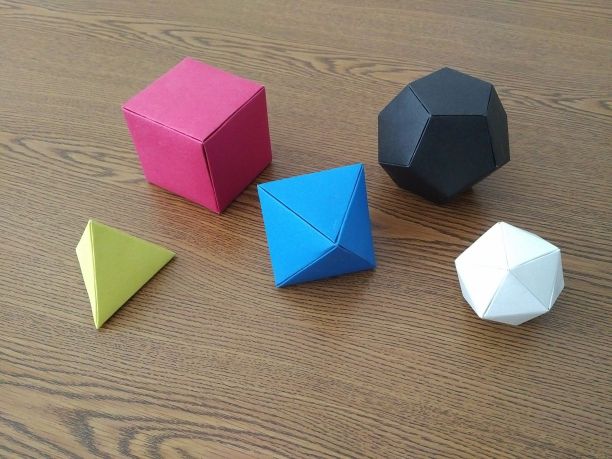

The Platonic solids are solids that like each other just as friends. They are also defined by the property that all of their faces are identical regular polygons, and all of their vertices are identical. There are exactly five of them, and proving that these five are the only possibilities is a common activity for geometry students. They hold special significance for me because, in addition to the pentagonal trapezohedron, they are the shapes of a standard set of polyhedral dice.

I experience mild associative synesthesia which causes me to associate certain colors with certain letters and shapes. The colors that I chose for these polyhedra are what my brain has decided are the "correct" colors.

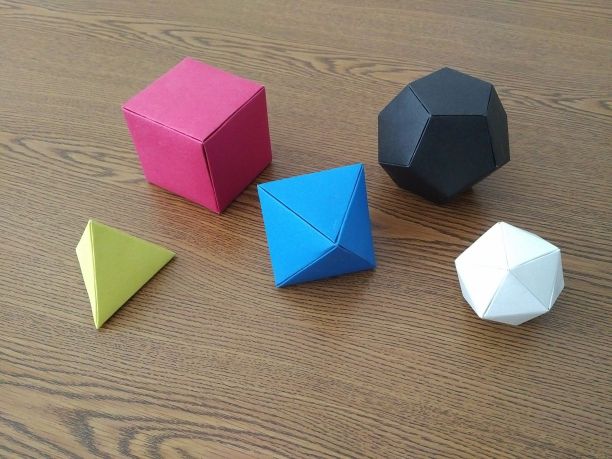

The tetrahedron (d4) is the 3D member of the simplex series, defined by the property that all of its vertices are equidistant from each other. Because that property is easy to generalize to any number of dimensions, there exists an analog of the tetrahedron in every possible number of dimensions (the 2D analog is an equilateral triangle). They are also extremely important in geology since silicon-oxygen tetrahedra form the building blocks of silicate minerals, which make up most of Earth's crust.

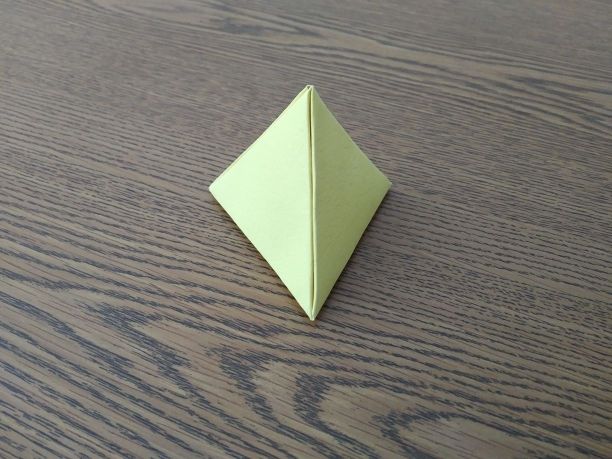

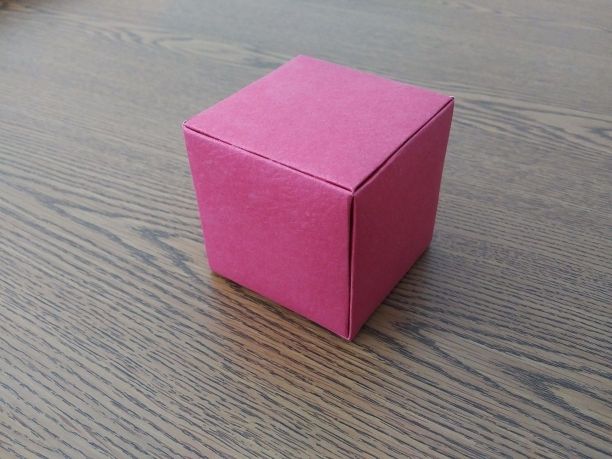

The hexahedron (d6), which some people insist on calling a "cube", was the first papercraft model I made. Its main distinguishing property is that it stacks very nicely, and can be used to tile all of 3D space (although the stellated rhombic dodecahedron does, as well, and is more interesting to look at). Its multidimensional generalization is the hypercube, which includes the 2D square and the 4D tesseract.

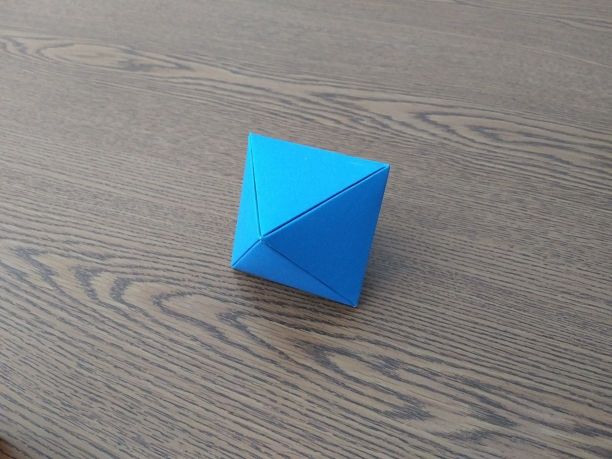

The octahedron (d8) is the dual of the cube, and is essentially what you would get if you converted all of a cube's vertices to faces and faces to vertices. This process also generalizes to higher-dimensional space, and there is an analog of the octahedron in all dimensions.

The dodecahedron (d12) is in my opinion the coolest-looking Platonic solid, and its 4D generalization, the 120-cell, is my favorite regular polytope. It also holds special significance within graph theory because of the Travellers Dodecahedron puzzle which led to the study of Hamiltonian paths.

The icosahedron (d20) has the most faces of any Platonic solid. It is made up of 20 triangles, and its 4D analog, the 600-cell, is made up of 600 tetrahedra. It is fairly round and is often used as the basis of geodesic domes.

You may very well be asking yourself why my icosahedron is so much smaller than all of the other shapes. That is an excellent question.

The Archimedean solids are polyhedra whose faces are made up of regular polygons and whose vertices are all identical, but unlike the Platonic solids the faces do not all need to be the same regular polygon. The Platonic solids, themselves, are usually excluded from the group, as are prisms and antiprisms (in order to prevent them from mutually annihilating each other when they touch).

Depending on how, specifically, the "identical vertex" requirement is defined, there are 13 or 14 Archimedean solids. That would have taken rather a lot of time to make, so I had to pick just a few of my favorites.

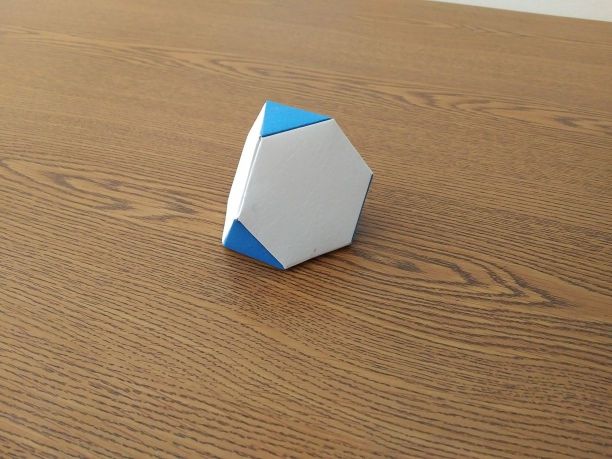

Like many of the Archimedean solids, the truncated tetrahedron is created by snipping the corners off of a Platonic solid in a way that leaves all of the exposed faces as regular polygons. In this case we have truncated the vertices of a tetrahedron just enough to turn the former triangular faces into regular hexagons.

Some polyhedral die makers have taken to replacing the standard tetrahedral d4 with the truncated tetrahedron, both because it is rounder (and thus rolls better) and because it always has a face on top (and thus can have a number printed on top).

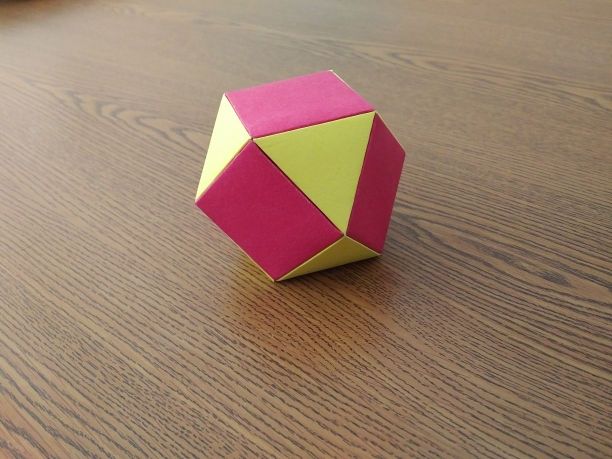

The cuboctahedron is a good illustration of the fact that the cube and the octahedron are duals of each other. It can be formed by truncating either a cube or an octahedron just enough for all of the cuts to meet. In this case the red faces correspond to the cube while the yellow faces correspond to the octahedron. If we were to continue truncating the cube until its original faces were completely gone we would be left with just an octahedron, and vice-versa.

Equivalently, it can be formed by separating the faces of either a cube or an octahedron, rotating them, and reattaching them to leave either triangular (for the cube) or square (for the octahedron) gaps, which are then converted into faces.

I decided to include the truncated icosidodecahedron purely because it is the largest Archimedean solid (in terms of number of faces, which is 62), and I knew that if I could only make a limited set, I might as well include the biggest boy. This model is a bit smaller than a soccer ball. Unfortunately its large number of faces means that it is quite round, and thus does not look especially like a polyhedron. I have also learned from experience that it is easily crushed if someone leans on it.

Polyhedral compounds are enclosed collections of polyhedral buildings. They are also shapes made by merging several polyhedra with a common center, usually in a way that preserves some interesting symmetry. I like them because they remind me of crystal twinning. The paper versions also present an interesting optical illusion where, by making certain pieces of paper line up and making them the same color, a bunch of completely separate pieces can appear to form a solid shape.

Much like the cuboctahedron above, the compound of a cube and an octahedron shows off the dual relationship between the cube and the octahedron. This shape happens to be equivalent to a stellated cuboctahedron, and if you were to sand down the triangular and square pyramids that make up its surface you would end up with a cuboctahedron.

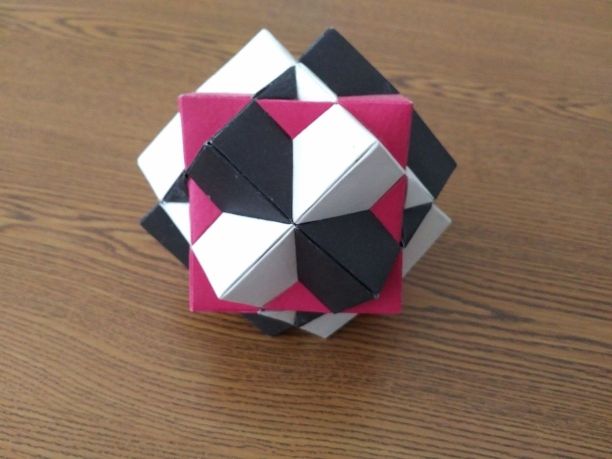

This is the crown jewel of the collection. It depicts three cubes that have been rotated and superimposed on top of each other. It contains the most separate pieces and took the longest to make out of any of my polyhedral models. It also appears in one of my favorite works of art: Waterfall, by M.C. Escher. I used to have a print of that lithograph posted on the wall above my desk, and I would stare at it every day to try to figure out what it was and what kinds of symmetries it possessed.

Incidentally, the other polyhedron featured in Waterfall is a stellated rhombic dodecahedron, the dual of the compound of 3 cubes. It is also known as "Escher's solid" because it has appeared in several of his works.

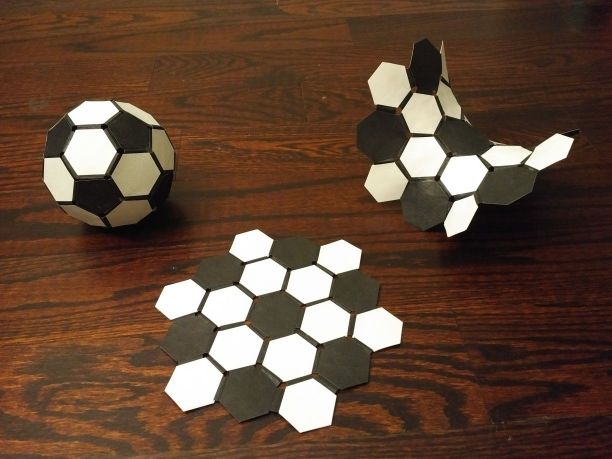

This is mostly meant as a visual gag featuring an elliptic, Euclidean, and hyperbolic soccer ball, but it comes from a thought exercise commonly used to introduce people to the idea of positively and negatively curved spaces. A standard soccer ball (shown on the left) is made up of black pentagonal panels, each surrounded on all sides by white hexagonal panels (this happens to be a truncated icosahedron).

What would happen if we tried to do the same thing, but using 6-sided hexagonal black panels instead of 5-sided pentagonal ones? Having 5 hexagons meet at every panel gave us a round, positively curved ball since we had to squeeze them together to get them to meet, but for 6 hexagons they already meet with no squeezing required. The result would be a completely flat ball (shown in the center), and unlike the positively curved version which curves around to meet itself and close itself off, the zero-curvature ball can potentially be extended in all directions forever. Unfortunately I do not have infinite space or paper or time, so I stopped after three layers.

Now what would happen if we tried using 7-sided heptagonal black panels? 7 hexagons is more than will fit together in the plane, and attempting to surround a heptagon with hexagons results in overlap. Rather than having to squeeze shut a gap as we did for 5 hexagons, now we have to spread the entire shape apart to make enough room to join everything. As with the positively curved ball this requires us to lift some things out of the plane, but this time the resulting object seems to want to be shaped like a saddle (or a Pringle) rather than a bowl. This is negative curvature (shown on the right), and like the zero-curvature case it can potentially be extended in all directions forever, but unlike the zero-curvature case it expands much more quickly as we move away from the center. If this model were to include a few more layers surrounding the center, the number of panels required would increase exponentially and the model would begin to look scrunchier.

If you would like to see how to properly make papercraft polyhedra, I would recommend you check out polyhedra.net and How to Build Polyhedra. Otherwise, read on. I do not have any raw talent for papercraft, but I more than make up for it in tenacity, and I was able to create the projects listed above after many hours of labor. As with all things, it will probably take you an unexpectedly long time when you first start out, but after you learn how to assembly line everything it will get faster.

If you look up designs for papercraft polyhedra, you will often find ones which consist mostly of a polyhedral net with tabs attached, which will mean that some edges are just creases while others are glued together. I am not a fan of how that looks since I like for all of the edges to be the same, so instead I simply cut out all of the faces separately with their own sets of tabs attached on each side. This is not strictly necessary, since a tabbed face could be glued to an untabbed face, but I like the look of the slight gap left when two tabs are glued together. I then crease the tabs and glue them together inside the shape. Here is what the inside looks like:

Using this technique you do not need a net and instead only a template for each face. I begin by cutting out a master copy of the face's shape (sans tabs) to use as a template, and then trace around it with a pencil to draw a bunch of identical copies for all of the individual faces. The traced faces need to be separated by a centimeter or so to leave room for the tabs. The tabs, themselves, do not need to be traced since they will all be hidden and need not be identical, therefore you can simply eyeball their shape separately for each face. After cutting them out, crease the tabs back using a ruler so that the face, itself, is well-defined.

Gluing everything together is relatively straightforward, albeit time-consuming. I use standard school glue. Apply a very thin layer of glue to one tab and press and hold it very firmly against another for a few seconds, then let it dry for a few minutes before working with the same shape again. I begin with one main face and then generally add layers around it, first making a bowl shape and then eventually curving around until everything meets at the opposite face. For non-convex polyhedra, I might instead begin by assembling some separate components and then assembling them (like the pyramids of the compound cube and octahedron). Obviously you will not be able to hold together the tabs of the last few faces since they will be closed off inside the shape, so instead you may need to pour a thin bead of glue into the final few edges and wipe away the excess with your finger.

The non-Euclidean soccer balls above were constructed slightly differently, partly because they needed to be flexible, and partly because both sides are visible and thus tabs could not be hidden away on the interior. These were made by cutting out panels with no tabs and sandwiching small rectangles of black paper between them to act as hinges. This results in the panels all being slightly separated from each other. This was not strictly necessary for the spherical ball, which does not need to flex and has a hidden interior, but I did it anyways so that the three pieces would match.